A tribute to the magnificent beasts that walk among us

© Peter DeArmond

A tribute to the magnificent beasts that walk among us

© Peter DeArmond

Here’s one of the favorite clips: Two young bulls brawling in the waters of Cub Lake:

Here are the most-watched elk film clips from (over 100 hours of film condensed to 8 minutes):

Full screen view

How the elk arrived, and eventually thrived, away from their home in Yellowstone

Rocky Mountain elk are not native to this state, according to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW). So how did these magnificent creatures get here?

In 1966 the Department of Fish and Game (as it was then called) issued a permit to Rex Ellsworth, who owned a large ranch in the area that is now known as Stallion Springs, to release up to 300 Rocky Mountain Elk on a fenced portion of his property. Ellsworth had arranged to import the elk from Yellowstone National Park with the intention to start a game farm.

By 1967, 290 elk had been shipped from Yellowstone, but only 277 survived to be released inside the ranch enclosure. After that, according to the DFW, many elk — up to 125 — died from “capture stress, transport, and confinement” and disease brought on from stress. Later that year elk began escaping because of the lack of fence maintenance. Some wandered to the south onto Tejon Ranch property, some stayed in the Stallion Springs area and some traveled north to the Fickert Ranch area, which is now known as Bear Valley Springs. (State legislation passed in 1979 prohibited any future importing of elk into California for game farms and also outlawed the removal or sale of their antlers for commercial purposes.) Mr. Ellsworth sold his ranch in 1969, and it became the residential development of Stallion Springs.

This was not the only place where Rocky Mountain Elk have been imported to California. In 1913, the Redding Elks Club purchased 50 Rocky Mountain elk from Yellowstone National Park for release in the Pit River area of Shasta County. The initial release apparently was augmented shortly thereafter by the accidental release of 24 elk from a stalled train in the Sacramento River Canyon. Rocky Mountain elk are still found in parts of Shasta County today.

The latest figures provided by the DFW in 2018 indicate that about 1,500 Rocky Mountain elk survive in California today. Most of them are in northern California, and an estimated 300 are in the Tehachapi Mountains. The only place where Rocky Mountain elk can be hunted in Southern California is on the Tejon Ranch, and then only with special permits, which are allowed through the DFW’s Private Lands Management Program (PLM). In exchange for conducting habitat improvement projects on their land that benefit wildlife, landowners (such as Tejon) can receive special PLM elk tags each year. The numbers and types of tags correspond to the population level of elk and the current conditions on the ranch. Elk in this area may have an earlier rutting season due to the warmer weather in Southern California.

The DFW formed what it calls a “Tejon Rocky Mountain Elk Management Unit” with boundaries that extend to the west by Interstate 5, to the south by Highway 138 in Los Angeles County, and to the north by Highway 58. The management goals for this Unit are to: 1) Improve elk habitat conditions and population levels in consideration of current habitat capacity, other land uses, and long term environmental changes; 2) enhance opportunities for the public to use and enjoy elk (e.g. hunting and wildlife viewing); and 3) alleviate human-elk conflicts. Speaking of which…

The bull elk that wander throughout the Tehachapi Mountains and Bear Valley Springs sometimes appear to be more tolerant or conditioned to the presence of humans than they normally would be in the wild. Elk need to get to their sources of food and water, meaning they inadvertently cross paths with humans. They may look slow and peaceful, but people forget that these are wild animals that can turn and attack at any time — and they can run amazingly fast when they want to. You’re supposed to stay 50 to 75 yards away from an elk, and the rangers who work for the Bear Valley Springs Association can issue a citation if you approach one.

Interesting facts about the Rocky Mountain Elk that live among us

First and foremost, even though the Rocky Mountain elk wander through our properties and onto the parks and golf course, we must remember to not approach them. These are wild animals and we don’t live in a petting zoo. The elk are simply searching for food and they usually tolerate our presence, but they are wild animals, always potentially dangerous. You’re supposed to stay 50 to 75 yards away from an elk, and you can be fined if you approach one.

Second, the Rocky Mountain elk that we see in the Tehachapi Mountains are not native to California. If you haven’t already read it, please see this article for the story on how they arrived here.

Most of the following information is from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, Yellowstone National Park and other sources:

• Of all the elk subspecies in North America, the Rocky Mountain elk have the largest antlers by far; they can reach 5 feet in length and weigh between 30 and 40 pounds on a mature bull. Bulls shed their antlers every year between January and April (usually between March and April) and start growing a new set of antlers right away. Elk antlers are the fastest-growing organic bone in the world, nearly an inch per day.

• New antlers are covered in a thick, fuzzy coating of skin called velvet. The blood that pumps through the veins in the velvet deposit calcium that make the antlers. Some biologists believe this blood flow to and from the antlers helps to keep the elk cool, like a radiator. By late summer, hormonal changes cause the blood flow to the antlers to stop; the velvet skin dies and starts to peel away. By September, the antlers are solid bone.

• It is not easy to tell precisely how old a bull elk is, but as a general guide: One-year-old bulls grow “spikes” that are 10 to 20 inches long; two-year-old bulls usually have slender antlers with 4 to 5 “points.” Antlers get thicker and longer each year. Bulls that are 4 years old and older often have 6 points. 11 or 12-year old bulls often grow the heaviest antlers; after that age, they diminish.

• When fully mature (about age five), a mature Rocky Mountain bull will weigh about 700 pounds, stand five feet tall at the shoulder, and measure eight feet from nose to tail. A mature Rocky Mountain elk cow, which does not have antlers, will weigh about 500 pounds and stand 4½ feet at the shoulder. I have been told by people who have lived in this area much longer than me that some bulls here can easily exceed 700 pounds.

• For most of the year, elk cows and bulls live apart from each other, usually in loose herds or groups. For example, there are about 12 to 18 bulls that roam over Bear Valley Springs most of the year. Rarely do they all come together; usually they split off in smaller groups. The cows tend to stay on the west side of Bear Mountain, and there are often several bulls that stay with them.

• During the rutting season, between September and November, the cows form harems with one or two mature bulls (or three, depending on the size of the cow herd). This also is the time when you may see elk bulls fighting more intensely. It’s a natural act and at times it appears they are just briefly “practicing” on each other. But when it gets serious, elk sometimes injure each other over mating rights.

• At times you may see a bull elk hold its head high, curl back its upper lip, grind its teeth and hiss softly. There are two possible reasons for this: First, the elk is telling others, “I’m walking here! I’m walking here! Don’t mess with me.” Second, depending on the season, you may be seeing the “flehmen response.” By curling their upper lips and lifting their heads, bulls expose a gland in the roof of their mouth that is used to detect estrus in elk cow urine, which in turn lets the bulls know when it’s time to go courting. (From the German word flehmen, to “implore,” which obviously has more than one meaning.)

• All elk cow herds are controlled not by a mature bull, but by an old, experienced cow that leads them where to eat and bed down for the day. These “herd” cows are protective and can make sneaking within observation range extremely difficult.

• A newborn elk calf weighs about 30 to 35 pounds. Calves usually are born in late May and early June, after about eight months of gestation. As with deer, elk calves are born spotted and scentless to protect from predators. They spend their first few weeks motionless while their mothers feed. On average, the Rocky Mountain elk lifespan is about 14 years.

• Elk eat grasses, forbs, shrubs, tree bark, twigs, acorns and, of course, in Bear Valley Springs they’ll feast on your fruit trees and other plants you try to protect. An elk's stomach has four chambers; the first stores food, and the other three digest it.

• Elk can be noisy, communicating danger quickly and identifying each other by sound. They may make a sound that seems like a bark, for a warning of danger. Or in general “conversation,” they may make chirps, mews and miscellaneous squeals. And a bull advertises his fitness to cows, warning other bulls to stay away, or announcing his readiness to fight, by bugling (a bellow escalating to squealing whistle ending with grunt).

• Scientifically speaking, elk belong to the Mammalian Order, in the family Cervidae. Other members of Cervidae include moose and the various deer species. Moose antlers are the only ones larger than the Rocky Mountain elk antlers.

• The smallest elk species and the only one native to California, the Tule elk, almost went extinct from over-hunting (10 were found to exist in the late 1870s in Kern County.) Thanks to conservation efforts, Tule elk survived and have been placed on preserves all over California. A mature Tule elk bull will weigh about 400 pounds.

• Bull elk love the water. In Bear Valley Springs in the summer, you can find them often dipping in Cub Lake, 4-Island Lake and Jack’s Hole.

• Roosevelt elk can be found in northern California, Oregon and Washington. A mature Roosevelt bull weighs about 900 pounds, so it is larger in body size than a Rocky Mountain elk. However, the Roosevelt elk antlers are noticeably smaller than those of the Rocky Mountain elk.

“How did you get that shot?”

My reply to that question is always, “I got lucky.” Really. That’s the dirty little secret: If you film enough, you’re bound to get something good once in a while. And I’ve learned there are some ways to create your own luck when filming wildlife.

If I want a good shot I can’t be in a hurry. I drive around these mountains from time to time, checking the many places where I know the elk like to hang out. When I find them, half the time they’re resting on the ground, doing nothing but chewing their cud. Sometimes I will stay in that place for hours, waiting for the elk to get up and do something interesting. I’m always learning and experience is the best teacher, along with a willingness to critically evaluate my own work. The more I go out and try, fail and evaluate, the luckier I get. More of my wildlife videos are at https://vimeo.com/peterdearmond/videos

There are occasions when it seems easy — after all, I live in a large mountain community where Rocky Mountain elk walk through all the time. But sometimes it can be frustrating, because I can’t control the scene or situation and I can’t ask the subjects to pose in the proper light. For me that’s a life lesson because, as Chuck Swindoll once said, “We are all faced with a series of great opportunities brilliantly disguised as impossible situations.”

“What do you use to shoot and edit?”

The video camera body is made by an Australian company, BlackMagic Design, and the model I have is called the URSA Mini 4.6k. I could never afford an Arri or a Red camera, but this model does the job for me at a fraction of the price. I use only three lenses right now, and the one I use for most wildlife shots is the Sigma 120-300mm f2.8. With the extender it’s about 400mm. This is heavy gear and I need to shoot everything on a tripod.

For editing, I use Final Cut Pro on an iMac attached via Thunderbolt 3 to a dedicated 16 terabyte 4-drive RAID array. RAID stands for Redundant Array of Independent Disks. The four drives are “striped” together to act as one super-fast disk, which you need to edit 4k video in real time. I buy and edit royalty-free music through different online sources.

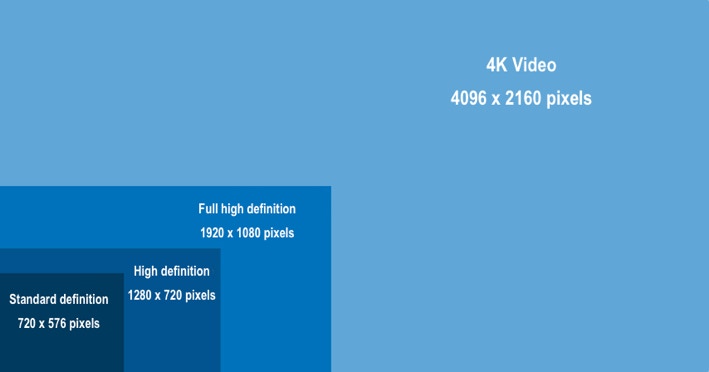

Below is a comparison chart that shows the difference in the various resolutions. The roundup video on this page is a very large file, so I saved it in 1080p instead of 4k so it would download faster. Most of my other 4K videos are uploaded to a site called vimeo.com, where 4K videos are supported and encouraged.

4K TVs show 4K content if the show is filmed in 4K. Content filmed in 1080p is upscaled to fit on a 4K TV

The most used HD today

The first HD used this

Our old TVs used this

“What is your professional background and experience?”

I’m one of those guys who enjoys doing different things, and probably never excels in any one of them. My personality type is an odd combination of adventuresome and analytical — I relish spontaneous interactions with total strangers and making new friends. But I’m also cursed (or blessed) with the childhood habit of always asking “why?” On the plus side, this combination of social affinity and analysis has made me a natural facilitator, something I still do today, and also may explain my rather twisted career path and diverse avocations.

Right after high school I flew from Bakersfield to Bavaria, bumming around central Europe alone, surviving awkward social encounters by speaking B-plus German. After that I was the editor of my community college newspaper, back in the days when newspapers were actually printed and read. Since then, in the intervening five decades I’ve jumped between many different pursuits, depending on what was interesting, challenging or available at the time. I have been a computer guru, daily newspaper reporter, editor, multimedia developer, DJ, business consultant, ballet dancer, cowboy, science historian, adjunct professor, facilitator and… next, maybe I’ll try out as a rodeo clown.

My first career passion was in print journalism, where I spent 20 years as a writer, editor, graphic designer and tech guy. Then I made a crazy switch and worked three years for California’s Fiscal Crisis and Management Assistance Team, followed by six years producing interactive media, videos and websites. Then I spent eight years directing the workplace training and business development programs at the Weill Institute of Bakersfield College. After that I tried to retire but failed miserably.

In addition to this I taught leadership courses at Fresno Pacific University and, I am proud to say, for five years I did training for Apple Inc. Then I tried to retire again and finally realized I’ll never retire.

I have a Bachelor of Science degree in Organizational Behavior and Master of Science degree in Education, with a specialty in training and performance improvement. I'm a certified facilitator through the National Curriculum and Training Institute in Real Colors and in Cognitive Behavior Change. I also did graduate work in Mass Communications at CSU Northridge. Blah blah blah.

Ever since my wife died seven years ago, I’ve stayed active as a way of coping. I have a cinematic digital film camera for a challenging science documentary project I started writing and filming some time ago (still working on it, too). When I moved to Bear Valley Springs 10 years ago I noticed the wildlife, especially the elk, and ever since I’ve been filming them just for fun. As everyone who lives in this area will tell you, we never get tired of seeing these magnificent, massive beasts who live among us.

If you have a comment or question you can contact me using the form below.

Peter DeArmond

Your name:

Comments or question:

Your e-mail address:

Your phone number:

(Required)

(Required)

(Required)

I’m using this e-mail form to help me cut down on spam. I will not share your information with anyone. I use your contact information only to reply to you regarding your question or comment.